Introducing Edwin

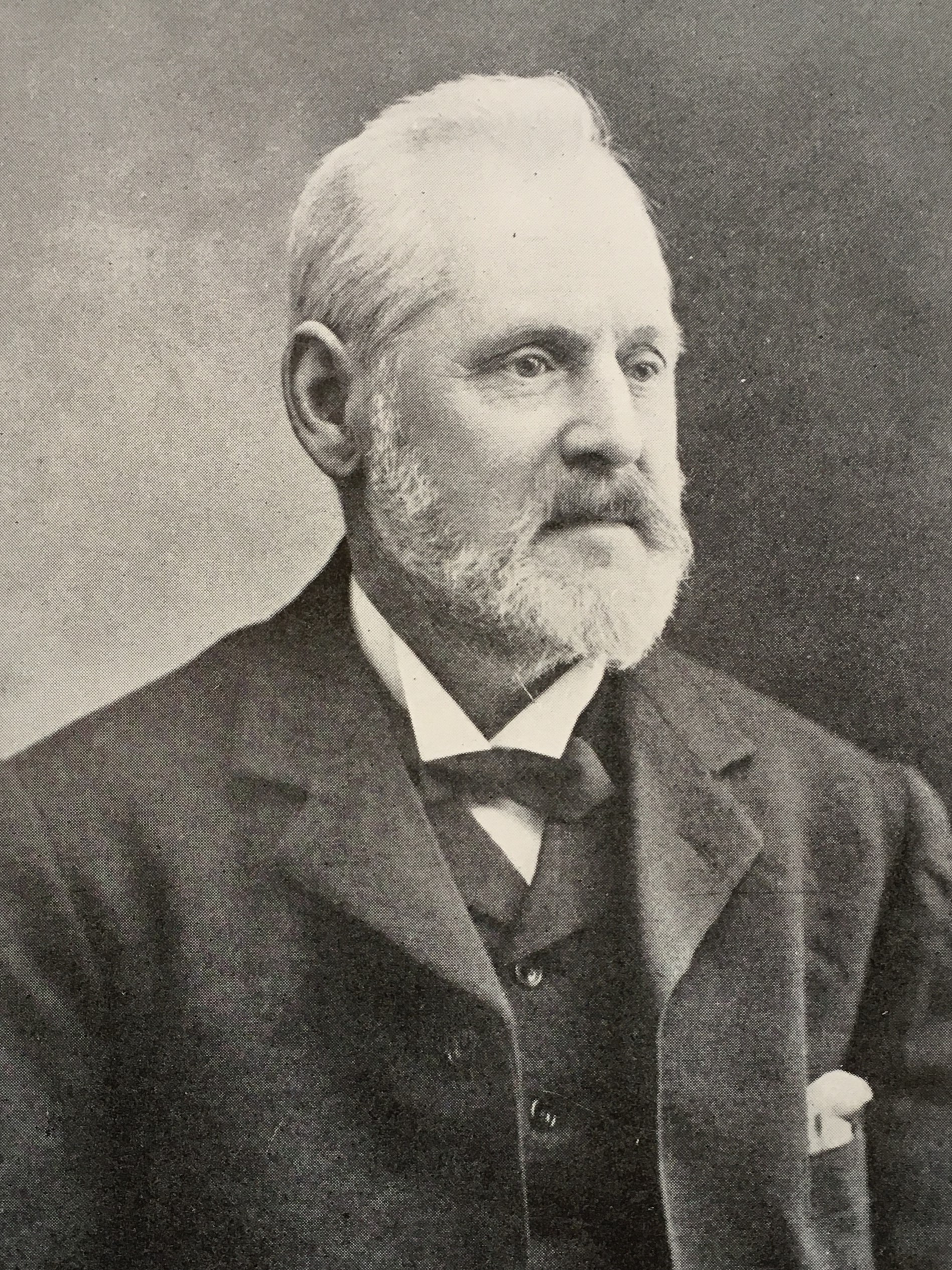

From 1879 onwards Edwin Butler, a prosperous grocer, kept a diary detailing his cycling adventures around Wokingham in the south of England.

Edwin fell in love with ‘the exhilarating and bracing effects of self-locomotion’ in his youth. In 1864, he and his older brother Henry rode one of the first four-wheel velocipedes. He then progressed to a boneshaker made entirely of gas piping, a machine that required no bell because ‘you could hear it a quarter of a mile off!’.

Edwin rode all year round, rain or shine, setting off in the early hours or returning late at night to fit his cycling around his working life. He would travel as far afield as the south coast and back on his iron-frame machine, along roads of gravel, sand and mud, often claiming to arrive home ‘as fresh as when I started’.

It was hot work then trundling those solid tyred ‘penny farthings’ along – though even so we often did 140 miles on them.

Yet Edwin was more than just a cyclist. He and his younger brother Tom designed and produced an innovative tricycle called the Omnicycle, patented in Tom’s name in 1879 and later manufactured under licence by the Birmingham Small Arms Company.

In 1903 Edwin took up motorcycling, and with no less enthusiasm. He and his older brother Henry were later dubbed ‘Britain’s oldest motorcyclists’, riding their Douglas machines until the ages of 79 and 83 respectively. Edwin passed away on 24 February 1931 aged 81 years. Reporting his death, the Reading Standard described him as a ‘wit and pioneer cyclist’.

Introducing the diaries

The story begins in April 1879, when Edwin had just turned 30. At the end of 1877, he had moved to the village of Eversley some six miles south of Wokingham to open a branch of the family grocery business there. But soon after, on 2 January 1878, he fell from his penny farthing and was badly injured. As he writes in the preamble to the first volume…

Then as soon as I got over here, I broke my kneecap and was so ill that I couldn’t collect my thoughts enough to keep a diary. But during the latter part of the three months that I was confined indoors, I carried on the diary, but as soon as I came back to Eversley, I commenced to work a little in the business again and this used up all my little strength. Then Tom and I commenced making a velocipede and this took up every minute of our spare time, and not having much energy all the year through, the poor diary was dropped.

The diaries then continue almost uninterrupted until the untimely death of Edwin’s wife Bertha in 1901, after which they become more sporadic. They cover his home and social life, his work dealings and his regular attendance at Baptist church services. Above all, though, they are a comprehensive log of his cycle rides – a Victorian equivalent of the modern cycling tracking app Strava.

Edwin’s writings take us back to a time when the cycle – initially the ‘penny farthing’ and, for the less athletic, the tricycle, and later the modern-style safety bicycle – ruled the road. Indeed, Edwin spent the prime of his cycling life in a world almost entirely free of motor traffic. Even in the later years of the diaries, the sighting of a car was a newsworthy event…

Wokingham was aroused on Tuesday morning by the appearance of a motor car which was driven through the town from the direction of Bracknell towards Reading.

Reading Mercury, 26 December 1896

Edwin’s vivid descriptions make us feel like we’re there with him exploring the highways and byways of Victorian England. And his sharp observations, lyrical turns of phrase and gentle wit keep us entertained along the way.

Despite being written in neat longhand with barely a crossing-out, the journals are hard to decipher. Edwin was writing solely for himself, so the entries are often short on context. He uses words and phrases that are unfamiliar to the modern reader, and the names of people and places are sometimes illegible. We’ve done our best to render the diaries accurately here, but we’d be glad to hear from you if you spot any mistakes.

After Edwin died, the diaries were passed down to his second daughter Hilda and for years were in the safekeeping of her granddaughter Wendy. After Wendy became ill and had to move into a nursing home in 2021, they were rediscovered by her brother David. His wife Sandra then set about painstakingly transcribing them, a herculean task given that they run to over 400,000 words (more than Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, for example). We are deeply grateful to her for her efforts.

And so the diaries reached us, Edwin’s great-great-grandsons, Simon, Jonathan and Christopher, all keen cyclists ourselves. (Coincidence, or something stranger?) We feel strongly they will be of interest to a wider audience, so we have made them available here. This is a work in progress – to receive updates, please join our Facebook group:

The Omnicycle

The diaries provide the only first-hand account of the genesis of the Omnicycle, an innovative tricycle designed by Edwin and his brother Tom in the late 1870s. Read the full story here.

Supporting cast

Edwin’s diaries are populated with literally hundreds of characters – far too many to list exhaustively here. However, a knowledge of his inner circle makes the story a little easier to follow.

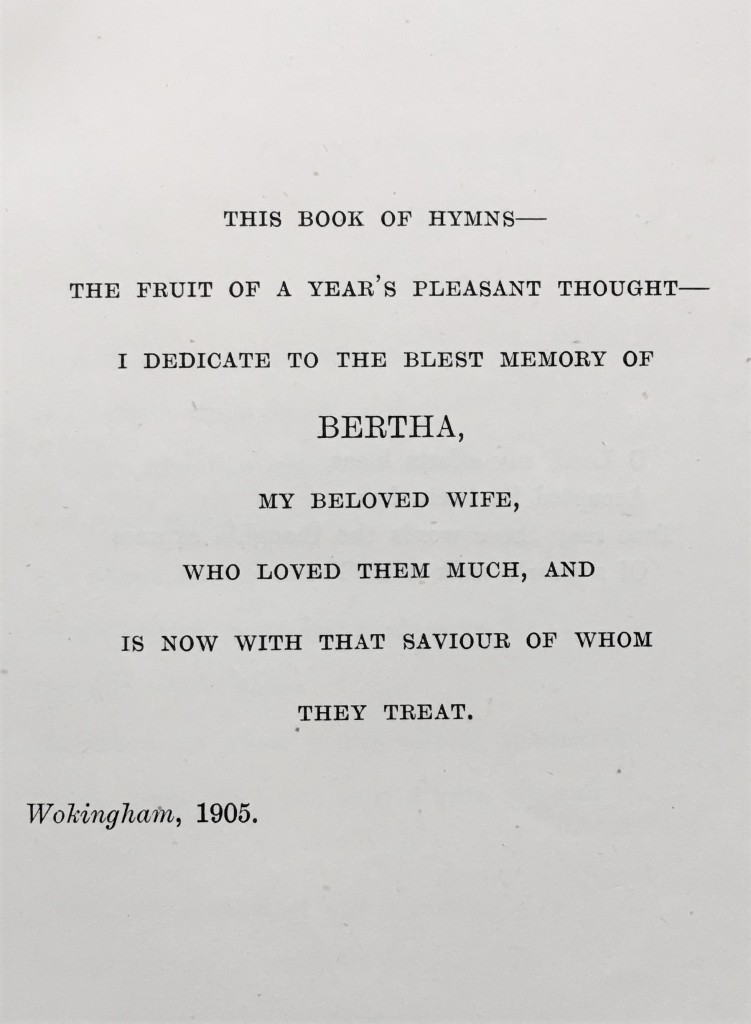

Edwin’s wife Bertha, whom he married in 1874, is the unsung hero of the diaries. That they exist at all is no doubt due in large measure to her. She would rise in the early hours to cook bacon for him ahead of his long trips. While he was out she would dutifully mind the children. And when he was scribbling away at his desk in the evenings she would presumably be washing his cycling clothes ready for the next ride.

A man of his time, Edwin did not wear his heart on his sleeve. He mentions Bertha frequently, but he doesn’t really reveal much about her or his feelings for her. Having said that, he certainly loved her. It can be no accident that the diaries become more sporadic after her death in 1901. In 1905 he published a book of self-penned hymns and dedicated them touchingly to her memory.

At the time the diaries begin in 1879 the couple have a three-year-old daughter Frances. A son, also called Edwin, comes along later the same year, and a second daughter, Hilda, arrives in 1885. For the most part, Edwin is quite unsentimental about them. Edwin junior receives no further mention after his death before the age of two in May 1881. And Hilda’s subsequent birth is marked only in passing with the cryptic entry…

A young lady came to see Bertha this evening.

Frances, who develops into quite a formidable cyclist herself in the later diaries, married Edward Herington in January 1902 and went on to have three children: Bertha (known by her second name Muriel), Alfred (who also died in infancy) and Wilfred. She died in 1940. Hilda had one child, Lois, with her husband Arthur Garnet (‘Garn’) Hall, whom she married in January 1909. She passed away in 1953.

Edwin’s most steadfast cycling – and, in later life, motorcycling – companion is his eldest brother Henry, who is married to Millie (née Rainbow) and runs the main family grocery business in the Market Place, Wokingham. Edwin is distraught when their daughter Mabel dies in October 1890.

Edwin also has three younger brothers (all single): John (who moves to Whitstable in 1880 to set up a business of his own and by 1883 is running a grocery in Hastings), Tom (who also leaves the Wokingham grocery in 1880 to work full-time on the Omnicycle, but, rather surprisingly, is not such a keen cyclist himself) and James (who appears to suffer from severe epilepsy).

Edwin’s older sister Mary is married to his friend George (‘Geo’) Woods, a Wokingham draper. The couple sell up their business in 1882 and later move to Hastings, where Geo becomes a well-known photographer. Mary dies in 1896.

taken by Mary’s husband George Woods in the early 1890s

(image credit: HASMG:T2017.50.HP1, Edwardian ladies on Hastings Pier, Hastings Museum & Art Gallery)

Bertha, Edwin’s wife, comes from another well-known Wokingham family, the Sales. Besides her parents James and Lucy (born Maynard), she has six siblings: Annie (married to James Donaldson), Minnie (married to watchmaker and fellow cyclist James Barkshire), Ada (who marries Fred Kent in 1882), George, Jamie and Eva (who later marries Henry Jelley).

Edwin often visits his aunt Ann Micklem (his father’s sister) in Burchett’s Green and his uncle Alfred Porter (his mother’s brother), a watchmaker in Hartley Row. His mother’s other siblings, Samuel Porter, also a watchmaker, and Matilda Porter, also feature occasionally in the the diaries.

On his birthday each year, Edwin receives a silk handkerchief from his aunt Caroline Saddler (born Butler). In 1892 he notes with great sadness the death by suicide of her husband John, an engraver who worked with William Turner and other major artists of the day.

Other members of the Sale, Rainbow, Micklem, Woods, Donaldson, Barkshire, Porter and Maynard clans naturally crop up regularly in the diaries. Philip Sale, for example, went on to become mayor of Wokingham in 1920.

(image credit: Wokingham’s Virtual Museum)

Edwin’s friends and cycling companions at various times also included watchmaker Henry Kemp, timber merchant George Phillips (mayor of Wokingham in 1894 and 1896), chemist William Rednall and draper Tyndale Heelas (mayor of Wokingham in 1891).

Among the most prominent customers of the Butler grocery were Sir William Cope at Bramshill House and Lady Glass at Warbrook House.

Edwin’s connections in the cycle trade – most notably industry mover and shaker Nahum Salamon – are covered separately in our history of the Omnicycle.

Edwin was a devout Baptist, so men of the cloth are often mentioned and their sermons rated. They include Reverends Woodrow, Scorey, Cave and Aldis. Medical practitioners also play an important role in the family’s life. Both Edwin and Bertha visit the eminent physician Sir James Paget in London. Doctors Haynes and Hicks of Wokingham and Dr Edward Wells of Reading also make appearances. Dentists Sprent, Morgan and Staveley all deal with Edwin’s recurring problems with ‘the face ache’.

And then there’s Mr Jelley, who, despite only making cameo appearances, is one of the most intriguing of all the characters in Edwin’s diaries…

Mr Jelley

Mr Jelley was a mercurial medic who befriended and attended to the Butler family in the 1880s and 90s. It turns out this was the same Henry Percy Jelley who later found fame – not to mention notoriety and prison time – as the ‘Threepenny Doctor of Hackney’. We recount the history of this extraordinary and controversial character here.

(image credit: The Threepenny Doctor. Dr Jelley of Hackney. London: Centreprise Trust, 1983. By kind permission of Ken Worpole)

Map

Leave a comment