Reciprocal action:

The story of the Butler Omnicycle

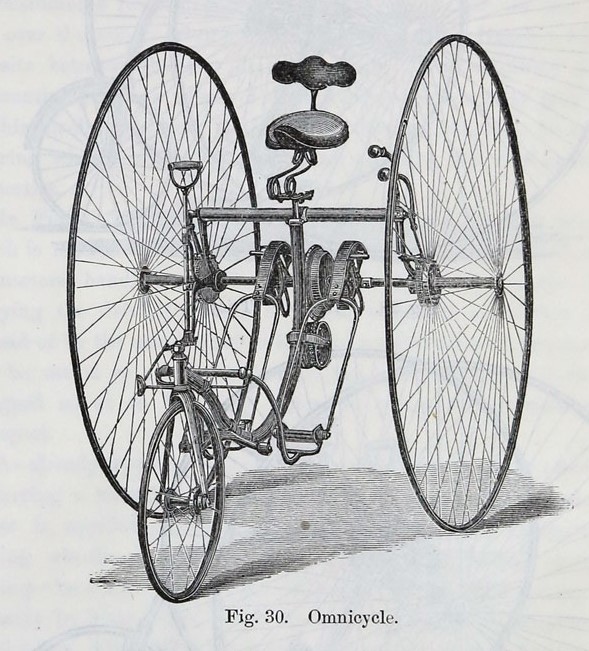

Thanks to Edwin Butler’s diaries, we can, for the first time, tell the full story of the Omnicycle (aka the ‘Squirrel Cage’) from its inception in rural Hampshire in 1878, through mass production in Birmingham in the 1880s, to its rapid slide into near obsolescence by the end of that decade.

To set the scene…

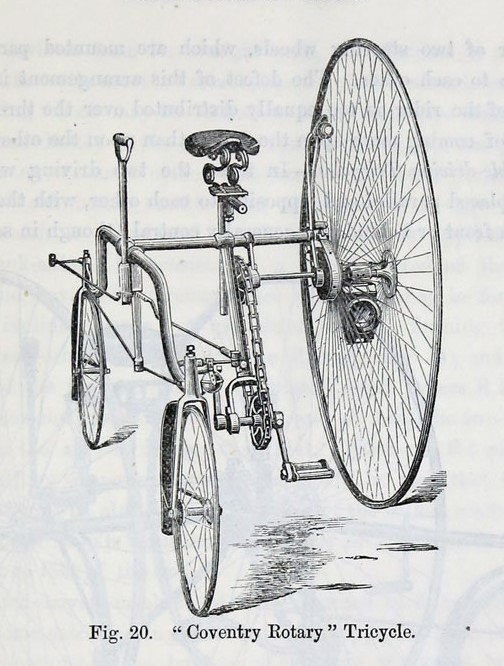

James Starley had in 1876 introduced the Coventry Lever Tricycle, sparking a tricycling craze in Britain. The modern-style ‘safety bicycle’ (with front and rear wheels of equal size) had yet to be invented, and the precarious penny-farthing, or high-wheeler, was mostly the preserve of daring young fellows. Tricycles, by contrast, could be ridden by less athletic gentlemen and even by ladies in long dresses.

By the time Tom and Edwin Butler started working on their design in 1878, tricycles were flooding onto the market. But their new three-wheeler – with a reciprocal rather than rotary drive action – would have a unique selling point: variable-power gearing combined with a freewheel. Faced with a hill, the rider would be able to change down rather than getting off and pushing. And on reaching the top, they could coast down the other side without having to lift their feet off the treadles. In this regard, the ‘Omnicycle’ would be years ahead of its time.

Who came up with the name, and when exactly, is lost to history, but the word ‘omnicycle’ first appears in Edwin’s diaries on 20 January 1880 and is used consistently from then on. It derives from the Greek ‘omnis’, meaning ‘all’, denoting that the machine – thanks to its adjustable gearing – could be ridden by anyone anywhere. It was certainly used occasionally by Edwin’s wife Bertha, making her something of a pioneer of women’s cycling.

Genesis

In the preamble to his first surviving diary, Edwin describes how, at the start of 1878, he broke his kneecap (while falling from his penny-farthing, it turns out) and was confined indoors for three months. The accident, he felt, had ended his chances of ever riding a bicycle again, so a tricycle offered him a chance of resuming his beloved pastime. This may have motivated him to come up with one of his own.

Bicycle Accident

On Wednesday evening, Jan. 2, as Mr. Edwin Butler, of the firm of Butler brothers grocers, of this town, was returning from their branch establishment, at Eversley, when near the Nine-mile-ride, on attempting to alight, he fell and broke his knee cap.

Reading Observer, Saturday, January 5, 1878

As soon as he was back on his feet in April 1878, Edwin and his younger brother Tom set to work on ‘plans of a velocipede to work without a crank’. The brothers were determined to ‘carry the thing through in the best manner possible regardless of expense’. They spent their evenings brainstorming at their home in the tiny Hampshire village of Eversley, where Edwin was running a branch of the family grocery business, until they had come up with the design of the main features of the machine.

By June, they had the plans of the frame and front wheel executed their satisfaction and took them to Timberlake and Co. in nearby Maidenhead, which had been building cycles under the Pilot brand since 1868. However, Henry Timberlake had by then sold the business to Alfred Hickling and Henry Hutchins. Timberlake introduced Edwin to Hickling, who, to Edwin’s great disappointment, refused to get involved and advised the brothers to abandon their plans, ‘as there were many makes now in the market, and further that all these amateur attempts (and there were hundreds of them) all resulted in failure and disappointment’.

Having been spurned by Hickling, the brothers felt that no other manufacturer would be interested, so they looked into making the machine themselves. However, Timberlake refused even to make components for them, and they soon also hit a dead end in finding a blacksmith to work with.

So, on 24 June 1878, Tom ventured into London with the plans and a list of cycle makers in a last-ditch attempt to save the project. His first port of call was William Keen at the Empress Bicycle Works in South Norwood, whom he felt was their best bet. As luck would have it, ‘Keen, without any word to the contrary, at once understood the job’ and agreed to take it on.

As well as the frame and front wheel, the new tricycle would need two large rear wheels. The hubs for these were cast in gunmetal at the Reading Iron Works. The brothers then had to turn the castings themselves. This turned out to be very time-consuming, as they had never operated a lathe before and even had to buy a forge to make their own cutting tools. After much trial and error, however, they were successful and sent the hubs off to Keen for him to build two 50-inch wheels.

Work could now start on the major innovation of the tricycle: the gearing that Tom would later patent. Most cycles of the time were single-speed, so on hilly terrain riders would regularly have to get off and push. The Omnicycle’s adjustable gears, not to mention its ratchet freewheel, would therefore give it a competitive edge.

Yet the mechanism proved tricky to construct. The expanding drum and friction clamps alone took three months to complete. In September, Edwin’s finger became badly infected. This left Tom to continue with the practical work alone for several months.

Keen had the frame and wheels ready in early November. These came to £10.9.0 – around £1,000 in today’s money. Tom then headed back into London to source springs and a tube for the axle. Despite visiting several wholesalers he was unable to get any good tubing, but he did manage to order springs from the Toledo Steel Company, a cycle works in Kentish Town.

By the end of February 1879, Tom had assembled the first prototype. The first test ride, though, was a failure. Tom’s efforts to propel the machine came to nothing and he had to drag it home after trundling along for a mere 100 yards. The brothers ‘went to bed very much disappointed and cast down’ and didn’t touch the machine again for a week or so.

After diagnosing and remedying the defect, they went for a second test ride and, to their delight, found that this time it went very well. More rounds of tweaking and testing followed, then Tom stripped the machine down, painted it and reassembled it ready for its first public outing.

On Good Friday, Edwin on the new tricycle and Tom on his high-wheel bicycle rode into nearby Wokingham to show off the fruits of their labour to the townspeople there.

Mr Wright had a short run on it and was fully convinced of its superiority over the crank machines, although during the making, he had been very much against it and had condemned the principle. After this, we had several runs on it and each time were more fully convinced of its being the right principle, and that we made up our minds to patent the machine should it compare favourably with the Coventry Tricycle.

The Coventry Rotary was one of the leading tricycles on the market. It was therefore vital that the Butlers’ new machine could compete with it, especially in terms of speed. On 22 April, they borrowed a Rotary belonging to Rev. John Matthews, minister at Wokingham Baptist Church, and conducted a road test. The new trike won hands down. No matter how hard Tom pedalled the Coventry, Edwin was comfortably able to pass him on their machine, ‘uphill, level ground or downhill’. Buoyed by this success, the brothers resolved to patent their design.

Patent

William Soper, a Reading-based gunmaker who had patented a breach-loading rifle in 1868, advised the Butlers to carry out a search at the Patent Office and to put the matter into the hands of a patent agent. On 28 April 1879, Tom, accompanied by older brother Henry, went up to London and found no patent there to interfere with their design, so Tom appointed Haseltine, Lake and Co. as their patent solicitors. Edwin meanwhile set about drawing up formal plans of the machine.

On 6 May, Tom took the completed plans to Haseltine and Lake in London and arranged for a provisional protection of the design for a fee of £8.8.0. The draft protection arrived in Eversley on 12 May. Edwin made a few corrections and promptly returned it.

In the meantime, testing and development of the prototype continued. Tom reinforced the friction drum with steel plates, but it was still prone to slipping. There were also recurring problems with the drivetrain catgut snapping and the ratchet failing. At one point, the axle broke clean in two and had to be replaced.

Despite these teething troubles, the men were happy with the performance of the machine, as evidenced by the following reports from their test rides:

Tom worked up all the hills on his way to Basingstoke and back, a feat, I believe, no bicycle could accomplish.

In the afternoon, Tom started off on the velocipede for a 12 mile run on the Flats. In spite of a very strong wind, he accomplished the 12 miles in 1 hour 3 minutes 30 seconds.

In the evening I had a run on the velocipede to the Flats and 6 miles on them and then home. It was a very pleasant run and I enjoyed it very much, the machine travelling comfortably at 11 miles the hour.

Edwin spent the first half of June working up a new set of plans for the tricycle. Tom then took these in to Haseltine and Lake. However, he instructed them to proceed with the patent unaltered, ‘as he thought it best to carry the matter through first’. Edwin sent the solicitors a cheque for £6.0.0 to continue the work.

At this time, Edwin was accused of skulduggery by a competitor, Mr Whitehouse, after visiting his works in Reading with a view to buying treadles for the new machine’s reciprocal drive. Whitehouse felt Edwin had done so solely to spy on his cycle construction.

At the beginning of August, Henry Timberlake came to Eversley to see how work was progressing. After testing the machine, he declared himself very pleased with it and strongly advised the brothers to make it themselves. Word of the project was clearly getting around, as they were already starting to receive enquiries from potential buyers.

Edwin recorded receiving the Letters Patent for the Omnicycle gear mechanism in his diary entry of 12 August.

List of Letters Patent which passed the Great Seal on the 8th August, 1879…

The Commissioner of Patents’ Journal, 8 August 1879

1909. THOMAS BUTLER, of Eversley, in the county of Hants, for an invention of “Improvements in velocipedes.” – Dated 13th May, 1879.

The new tricycle underwent its first big distance trial on the first day of September, when Edwin – accompanied by Tom and their friend Philip Sale on bicycles – rode it 50 miles to Portsmouth (or Gosport, to be more precise). Apart from one unplanned stop to fix a snapped catgut, it passed with flying colours.

I did not get out of the velocipede to pull it (excepting for the large stones before Odiham) on any part of the journey, neither up or down hill. I rode every inch of the ground without any straining.

How did the Omnicycle work?

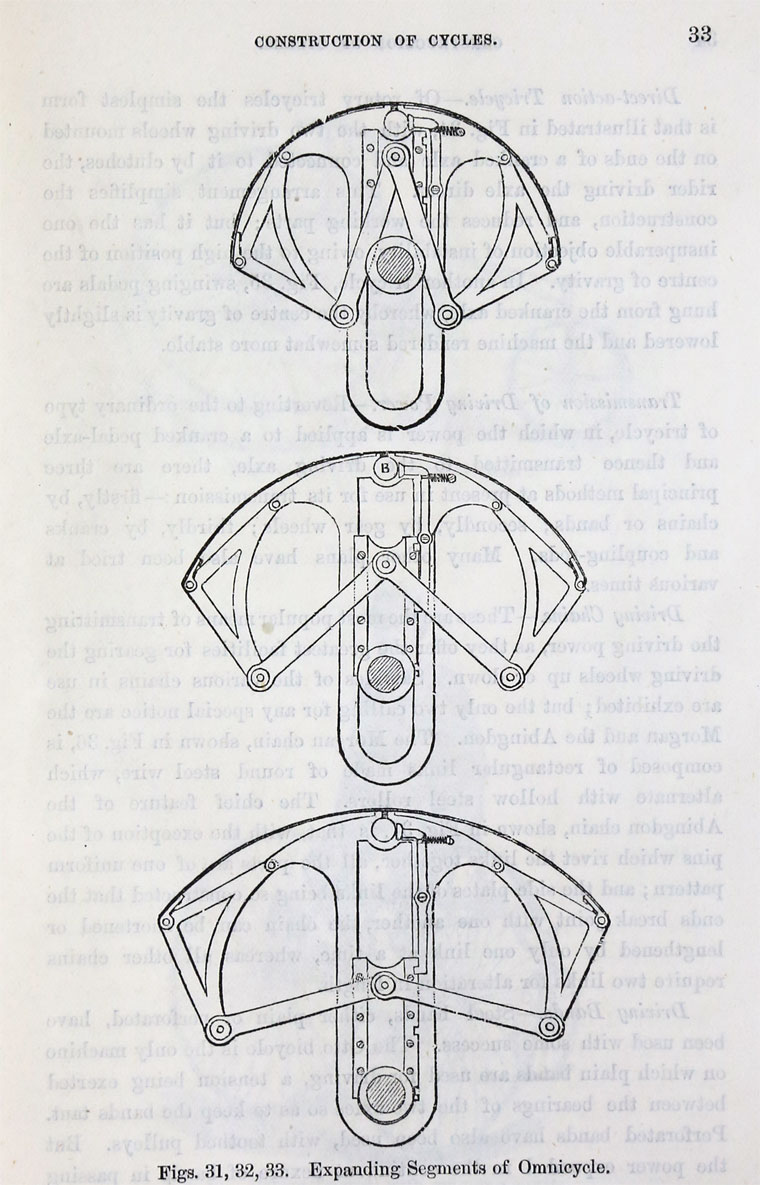

The Omnicycle segmental gearing with its to-and-fro treadle action was described in the winter 1960 issue of The Boneshaker as ‘one of the most peculiar and ingenious in an age of peculiar and ingenious devices’. It was explained neatly in 1885 by Robert Phillips in his paper On the Construction of Modern Cycles:

The pedal levers are connected by bands to two expanding segments, which are each connected to the driving axle by clutches, and to each other by a reversing apparatus, so that the forward movement of the one produces the backward movement of the other, and thus the descending pedal raises the other ready for the next stroke. The segments are constructed so that they can be expanded or contracted, so as to give greater or less leverage, as shown in Figs. 31, 32, and 33, in which the segments are represented at their extreme and mean radii.

The eminent English physicist Sir Charles Vernon Boys demonstrated the Omnicycle gear in a lecture Bicycles and Tricycles in Theory and Practice which he gave at the Royal Institute in 1884 and subsequently published in Nature (20 March 1884). He noted that expanding drums were employed ‘so that the power may be applied with different degrees of leverage according to circumstances’. Dead points in the action were thus avoided.

The Wokingham works

By the end of August 1879, Tom and Edwin were looking for suitable premises in Wokingham for production of their new machine. On 3 September, Tom put in an offer for Allaway’s workshop (exact location unknown, although we do know that by 1907 the ‘Wokingham Motor and Cycle Works’ had premises at 11 Market Place and 11 Peach Street), which was on the market for £300. The final price of £270 was agreed on 13 September. Work soon began on fitting out the space.

Tom took charge of the new works. He hired a foreman recommended by Timberlake and made trips to London and Birmingham to procure machinery and materials. Edwin meanwhile stayed in Eversley to run the grocery business, although he regularly dropped in at the works. The prototype remained with him and he continued to ride it in all conditions and at every opportunity. By 28 October he had ‘completed 1000 miles safely ridden without one single accident of any kind’.

On 12 November, Edwin received the ‘Complete Specification’ in the post and took it in to the works, where he, Tom and Henry discussed the various parts of the new machine. On his way back home, ‘when leaning forward to undo the brake one of the brake bar bearings gave way and nearly threw me out of the machine and sent it and me within an ace of the ditch. I received no injury except for a few knocks on the elbow.’

In November, Tom began work on a second machine. By 24 November it was ready to ride and he brought it over to Eversley, where he and Edwin briefly put it through its paces on rutted roads. Unfortunately, it broke down as he was heading back into Wokingham, the backbone separating from the arch.

Over the course of the winter, Tom continued to refine the design, for example by replacing the unreliable catgut with chains. By the end of February 1880, he had three Omnicycles painted, varnished and ready to be sold. Edwin then wrote a prospectus for them. By the time the proof came back on 19 March, Tom had already sold several machines. In early May, Edwin himself made a sale to Henry Padwick, a schoolmaster from the nearby village of Yateley. At the start of June, Edwin took receipt of a 54-inch wheel Omnicycle for his own use and returned the first prototype to Tom.

On 22 May, Tom and Edwin rode from Wokingham to a busy bicycle meet at Hampton Court. In Edwin’s words, ‘we exhibited our omnicycles to a great many and they were very much admired by several’.

Sales were no doubt also boosted by two letters of recommendation published in the cycling press of the day, one from Edwin’s friend Rev. Matthews in Bicycling News in June and another from J. G. Lyne of the Bicycle Touring Club:

In Cycling for April last ‘Cyclops’ states that he is waiting for a tricycle that will carry him uphill as easily as a two-wheeler. I have great pleasure in telling him, and all whom it may concern, that I have lately ridden a marvellous machine, that really and truly goes up any hill far easier than any bicycle yet made. It works without cranks, and by simply pulling a small handle and spring it gives three different rates of speed, and power enough to ascend a mountain, provided the paths were wide enough. I am not in the slightest degree connected in any way with this machine.

Cycling, July 1880

On 12 June, the Coventry Machinists Company, Britain’s first and leading cycle maker, wrote to Tom asking him for permission to make the Omnicycle under licence. This is where one Nahum Salamon enters our story…

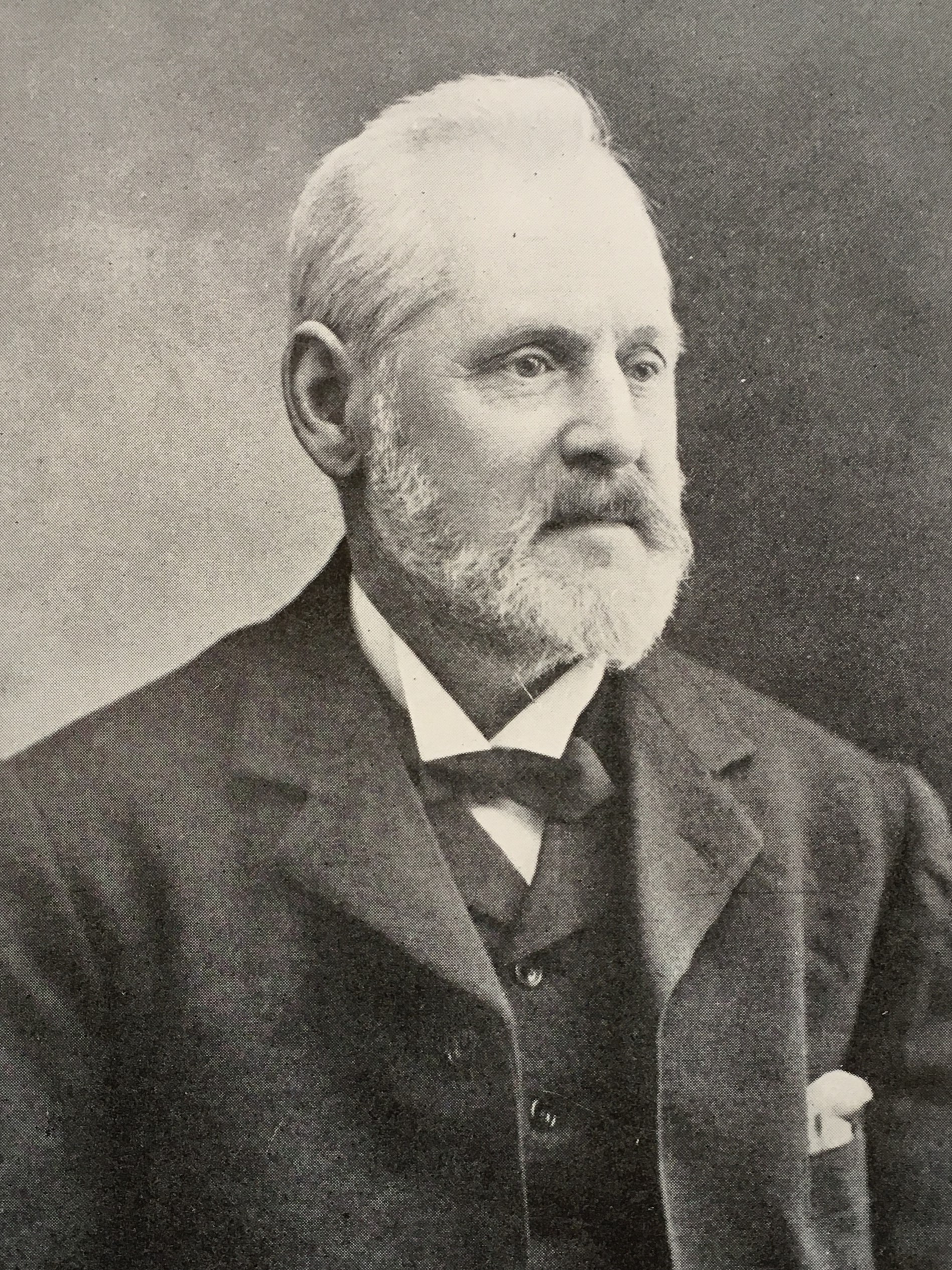

Nahum Salamon

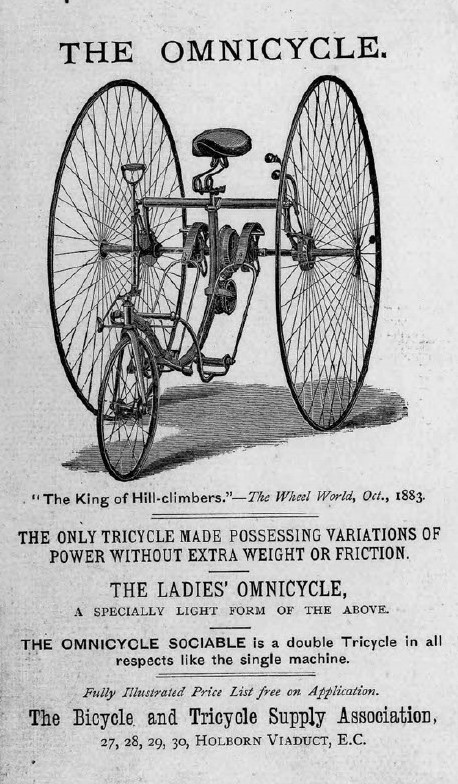

Nahum Salamon (c. 1830–1900) is credited with introducing the Howe sewing machine to Britain from the USA in 1859. During the 1870s, he became a mover and shaker of the British cycle industry as manager of the Coventry Machinists Co. (CMC). Early in 1881, he set up the Bicycle and Tricycle Supply Association, a retail operation trading at Holborn Viaduct in London, where many cycle manufacturers also had offices. He filed a number of patents and had bicycles made by Singer & Co. in Coventry. However, he was clearly looking to add a tricycle to his product portfolio.

Salamon was still at CMC when they contacted Tom in June 1880. However, he was plainly already acting in his own interests, for just two weeks later he wrote privately to Tom to enquire about the Omnicycle. The two agreed that Tom and Edwin should come up to London and show it off. And so, on 5 July, the brothers made their way to Salamon’s home, the rather grand Thornton House in Atkins Road, Clapham, South London.

This first encounter was not entirely auspicious. Edwin developed a splitting headache while riding the machine over from Barnes railway station. On arriving in Clapham, he ‘came over bilious’ and was unable to eat any of the meal Salamon had kindly prepared for his visitors. After dinner, while out cycling with Salamon’s son David, he threw up at the bottom of a descent. On top of that, the parlous state of the roads made the going too slow for the brothers to show off the Omnicycle to its best advantage. On returning to Thornton House after a ride of seven miles, they arranged for Salamon junior to come over to Wokingham for another test ride the next day.

This second trial was more successful. The three gentlemen averaged almost 10 mph on an eight and a quarter mile course between the Wellington Monument and Basingstoke and – after a rest and a ginger beer – put in a wind-assisted more than 12 mph on the return run. Over one three-mile stretch they clocked almost 20 mph. Young Salamon declared himself very pleased with the performance of the Omnicycle as he boarded the train to report back to his father.

Just two days later, Tom received a letter from Salamon asking for terms and conditions. After seeking clarification, the Butlers wrote back on 12 July setting out their offer: either a lump sum of £4,000 (around £375,000 in today’s money) or £1,500 up front and ten shillings per sale. Salamon wrote back refusing the terms and the negotiations broke down.

Edwin continued to ride the Omnicycle, clocking up a personal best of 307 miles covered in two weeks in the first half of August. Towards the end of that month, he called in to see Tom, ‘who gave me the dumps about his business’. The project was clearly in need of a financial backer.

On 13 October, Salamon summoned Tom back to London. Negotiations continued in parallel with the development of a ‘new pattern’ Omnicycle for the 1881 cycling season. Tom had the prototype ready to roll by mid-January. Whether this was the same as the (frankly puzzling) ‘one-wheeled’ machine also mentioned by Edwin in the diaries at the time is not clear.

By the start of April 1881, Tom was employing eight men and two boys at his works. As well as the upgraded Omnicycle, he was selling a touring bicycle, which he advertised in that year’s edition of The ‘Indispensable’ Bicyclist’s Handbook by Henry Sturmey.

In May 1881, Edwin and Tom discussed terms offered directly by BSA itself, but no more details are given in the diaries.

By this stage, the Omnicycle was establishing itself on the racing scene in Britain. On 25 June, Percy G. Hebblethwaite of the Dewsbury Bicycle Club, rode an Omni to second place behind G. L. Hillier in wet and windy conditions at the Tricycle Association Championship, after the favourite, Frank Allnutt of Redhill, also an omnicyclist, retired due to illness. A couple of weeks later, on 8–9 July, Hebblethwaite beat Allnutt’s record for the longest 24-hour tricycle ride by covering 139 miles on the same machine.

Also in July, Egbert Tegetmeier, Cycling Editor of The Field, visited Wokingham with a friend and discussed the design of the Omni with the Butlers. At the start of September 1881, Tom placed an advertisement in the same magazine offering his business for sale. In mid-November, however, Salamon came to the rescue with a new offer. On 16 December, the two signed an agreement for Salamon to make the Omnicycle under licence. Unfortunately, Edwin did not record the terms for posterity in his diary.

At the end of 1881, Salamon subcontracted the manufacture of the machines to the Birmingham Small Arms Company. BSA agreed to supply him with 200 Omnicycles at £13.10.0 each and a further 360 at £16.0.0 each. He would then retail them at £25.0.0 without extras (more than £2,300 at today’s prices). And so, a full year and a half after Salamon had first expressed an interest, the Omnicycle went into mass production.

BSA

BSA had been mass-producing small arms since 1861 but did not diversify into cycle making until 1880, when it acquired the licence to produce the Otto, a curious contraption (later termed a ‘dicycle’) on which the rider perched between two parallel wheels. By the time it launched production of the Omnicycle for Salamon, the firm was marketing two bicycles and two tricycles of its own. It continued to make cycles until 1957, when Raleigh bought that side of its business.

The simple fact that a machine is turned out by the Birmingham Small Arms Co. is a guarantee that both the materials and workmanship are the best to be obtained.

Athletic News, 1882

(Science Museum, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7708698, via Wikimedia Commons)

BSA’s machining equipment and experience meant it could turn out parts of high quality cheaply and quickly. It soon had machines ready for Salamon to unveil at the biggest trade event of the year, the Stanley Cycle Show, held at the Agricultural Hall in London on 9–18 February 1882. Edwin attended the show on 14 February. He was impressed by the large variety of tricycles on offer but wrote in his diary that ‘none caused so much attention as the omnicycle’.

The initial reviews of the BSA machine were glowing. ‘The Omnicycle…is sure to command its share of public patronage,’ wrote Athletic News. John Browning, Vice-President of the Tricycle Association, went even further in his report for the recently founded popular science weekly Knowledge, declaring it to be one of the six best new tricycles of the 20 or 30 introduced in 1882. ‘The Improved Omnicycle solves in the best manner yet contrived the application of speed-changing gear to a tricycle,’ he added.

In a discussion of the relative merits of various ‘tricycles for country practice’ in the British Medical Journal of 27 May 1882, one correspondent recommended the Omnicycle ‘for those living in very hilly districts’ because of its variable gearing. Other letters published over the following year or two testify to its popularity among GPs of the day. Indeed, by 1884 it was being marketed as ‘the Tricycle for Medical Practitioners’.

The Butlers retained at least some say in the design of the Omnicycle. For example, Edwin was unhappy with the back action and told the BSA engineer so at the Stanley show. He designed a chain to use in place of the cog wheels in the drive. Salamon then ordered 67 of these, although he later decided cogs were preferable after all.

On 29 March, Tom and Edwin visited Salamon to check out the latest machine from Birmingham and they all felt it was ‘vastly too heavy’. By the end of September, Tom had got the weight of his Omnis down to 101 lb, but the machine was still no lightweight by comparison with the penny-farthings of the day, which typically tipped the scales at around 40 lb.

In late August, Tom received a royalty cheque for over £180 (equivalent to almost £17,000 today). Assuming that he was getting close to what he had asked for in his original offer, namely ten shillings per sale, this indicates that Salamon had shifted more than 350 units in those first six months or so.

By June 1882, the Butlers were already discussing entering into another agreement with Salamon. On 5 October, Tom received a letter from him asking for a five-year contract, and in mid-November the two men came to an arrangement ‘over which [Tom] was very pleased’.

Downsides and upgrades

For the 1883 season, Salamon introduced an upgraded Omnicycle, which took its place alongside more than 250 tricycles on the market. According to Edwin, Tom, too, had ‘a good stand of omnicycles’ of his own at that year’s Stanley Show, at which there were more tricycles than bicycles on view. The Tricyclists’ Indispensable Manual found the machine – by now retailing at £26.5.0 – to be ‘thoroughly well made and finely finished’. The Tricyclist of 29 July 1883 declared the Omni to be ‘second to none’ as a hill climber, if rather slower than a rotary-action tricycle on flat ground, and also praised its stability, steering and solid build. The response from the public was also mostly positive, going by readers’ letters to the press:

I was delighted with my choice, and I would strongly recommend it to anyone who, like myself, wished for a machine in the sense of a tonic.

It is a capital hill-climber.

I run mine in hilly country, and find it everything that can be desired.

With the ‘Omnicycle,’ hill-climbing, instead of being a toil, becomes somewhat of a pleasure.

Yet the Omnicycle was not without its detractors. In 1883, The Tricyclist called it ‘a machine about which there is perhaps more diversity of opinion than any other in the market’. The main brickbats were that it was heavier and slower than its rivals, and that it couldn’t go backwards.

We may premise that it is well known that the [BSA-made] Omnicycle of 1882, although improved in many points, was not as good as that of 1881, because it was considerably heavier, and connoisseurs of Omni’s sought out 1881 machines in preference to those of 1882’.

The Tricyclist, 20 July 1883

Salamon responded by cutting the weight of the 1883 model by a full 40 lb to 95 lb (thanks to a ‘lighter frame, lighter wheels and lighter works’, according to The Bicycling World) and by adding a reverse gear. The Tricyclist reported that ‘the Omni of 1883 is as much in advance of the Omni of 1881 in this point as the machine of 1882 was behind it’. Even so, some felt the gearing was tricky to operate. Others found it difficult to get used to the treadle action .

The sudden starting and stopping of the feet…make this type utterly unsuitable for obtaining anything more than a moderate speed.

C. Vernon Boys, Nature, 20 March 1884

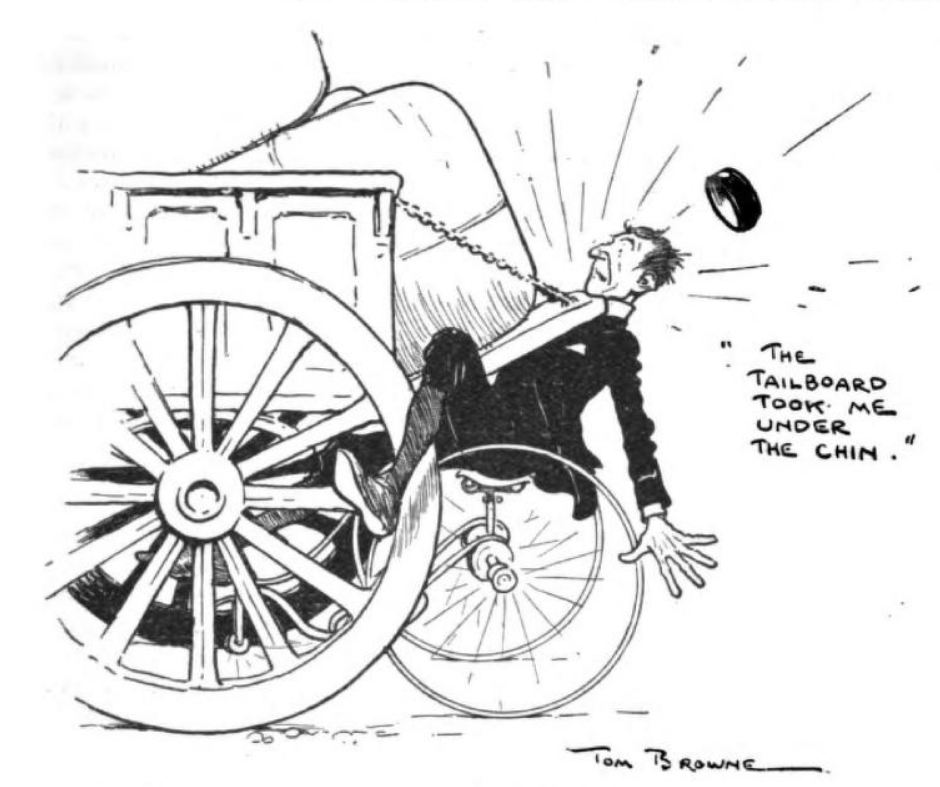

The drawbacks of the Omnicycle were later alluded to by Leonard Larkin in a humorous retrospective of the golden age of the tricycle, My Trikes – and Some More Bikes, published in The Strand Magazine of May 1903:

Does anybody remember the Omnicycle? I do, though my experience of it was limited to a half-mile ride in the City of London. The rider sat between equal-sized driving wheels and steered with a small wheel in front; and between that steering-wheel and the others there was about a quarter of a ton of the most ingenious mechanism ever seen on a cycle. You pedalled, not round and round, nor even up and down, but obliquely, downward and forward, and each tread pulled a strap which helped to pull all the machinery on the axle. There were so many advantages in this mass of ingenuity that I have forgotten them all except one, which was that the omnicycle couldn’t possibly betray you by running backward when you were ascending a steep hill. I was so delighted and confused by the explanation of the complicated merits of all this machinery that I cut it short by mounting and riding off into the traffic. There was a certain mental gratification in the reflection that I was setting all that vast conglomeration of engineering genius to work by the mere effort of my own personal legs, and I spun along gaily till at last it was necessary to pull up behind a cart. I pulled up accordingly, with my nose about a foot away from the cart’s tailboard; and I made the appalling discovery that the reason the machine wouldn’t go backward on a hill was that it wouldn’t go backward at all, anywhere. Not only couldn’t you drive it backward with your feet, but you couldn’t shove it – the wheels wouldn’t turn that way. I had just time to realize the full significance of the improvement when the tailboard took me under the chin. It was my first back somersault, and I earnestly recommend any lady or gentleman who thinks of practising the feat to begin without a tailboard under the chin; it cramps the style.

An electric Omni?

In his 1994 History of the Electric Automobile, Ernest Henry Wakefield asserts that the Omnicycle was probably used to make the first English electric vehicle. On 3 November 1882, Knowledge reported that two English professors, William Ayrton and John Perry, had fitted a tricycle with electric motors and successfully demonstrated it in the City of London. According to Wakefield, they reversed the direction of travel so the steering wheel trailed rather than led. Knowledge concluded prophetically:

In the tricycle ridden by Professor Ayrton, the ordinary foot treadles were entirely absent, but with ordinary electric tricycles it may be desirable to leave the treadles, so that while electric propulsion alone is used on the level, the rider can, on going up a steep hill, supplement it by using the treadles, instead of, as at present with the ordinary non-electric tricycle, having to get out and ignominiously push his tricycle up the hill before him.

Decline

The beginning of the end of the Omnicycle can be traced to the 1885 Stanley Show. It was here that John Kemp Starley – nephew of James Starley, who, ironically, had started the tricycle boom back in 1876 – unveiled his game-changing Rover bicycle. With its same-sized wheels and chain drive to the rear wheel, the Rover was the first recognisably modern bicycle. Safer and easier to ride than the penny-farthing, yet faster, simpler and cheaper than the tricycle, it rendered both of them almost obsolescent at one fell swoop. On top of that, Starley patented only one minor part of his design, so within months his rivals were producing versions of their own. This fierce competition only hastened the demise of other styles of cycle. By the early 1890s, the ‘safety bicycle’ had become a means of transport for the masses.

(1901-6 Science Museum Group Collection Online

https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co25833/rover-safety-bicycle-1885-bicycle)

We haven’t been able to establish when BSA stopped producing Omnicycles. Tom went up to Birmingham in May 1884 to sort out a problem with the clutch, which suggests they were still making them then. The 1884 catalogue of the Bicycle and Tricycle Supply Association offered not only the standard Omnicycle, but also a lighter-weight ladies version and even a two-seater model called the ‘Sociable’. The company also exhibited the Omni at the 1886 Stanley Cycle Show, where it was described as an ‘older favourite’. And we know from Edwin’s records that Tom continued to make Omnicycles at least until 1890. But the trail then runs cold.

The Omnicycle does not feature in the diaries at all after 1891. In fact, mentions of it start to tail off rapidly in 1883. In June 1881, Edwin had started riding a high-wheel bicycle again for the first time since breaking his knee three and a half years earlier. He found it ‘easier than the omnicycle’ and so used the latter less often from then on. He also naturally became less involved in making and marketing the Omnicycle after Tom set up the works and Salamon bought the licence.

The last record we have of Edwin riding an Omnicycle dates from January 1891, when he borrowed Tom’s machine and rode it along a frozen stretch of canal near Basingstoke. It was his first Omni excursion for some time, and not one he enjoyed, ‘for my legs began to ache from the strange action, and the further I went, the more intolerable was the pain’.

I was very glad I came along [the frozen canal], as I may never have the opportunity to do the like again. I only regret I did not have a rotary machine, for it is so long since I worked the lever movement that the strange action quite paralyzed me.

The Omnicycle today

We’ve been doing some detective work to locate any Omnis still in existence. Three leads have emerged.

The first concerns an Omnicycle that was put up for sale at an auction held by H&H Classics at the Imperial War Museum on 10 October 2007. The ‘impressive’ machine – in original and rideable condition – had an estimated price of £18,000–£22,000 and went unsold. According to the auction website, it had been in the same ownership for the previous 45 years and was believed to be the only complete and working example. We have established that this Omnicycle is now in a private collection in the south of France.

(image reproduced by kind permission of H&H Classics)

The H&H Classics website goes on to say that ‘another [Omnicycle] is known to exist, which arrived at a museum in pieces and has stayed in the same state for nearly 100 years’. Edwin himself, when interviewed sometime around 1927 for a publication on Douglas motorcycles, said that an Omnicycle could be seen in South Kensington Museum, now the Science Museum in London.

In 1955, the Science Museum published a book The History and Development of Cycles by Cyril Francis Caunter, keeper of the museum’s road transport collections. The book is illustrated with photographs of the museum’s cycles, including one of an intact Omnicycle.

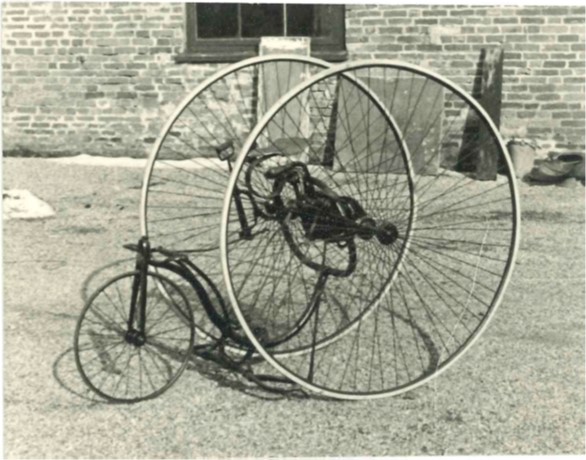

We ran an online search of the Science Museum’s collection and found two Omnicycles there, with object numbers 1918-188 and 1956-120. The Science Museum have kindly provided us with what little information they have about these machines. The 1918-188 machine was reportedly built by Singer and Company Limited to Thomas Butler’s patent, although there is nothing in the diaries to indicate that Singer ever made an Omnicycle. It has 49.5 inch wheels and weighs 141 lb, which suggests it might be an 1882 BSA model. Omnicycle 1956-120, which weighs 120 lb, was reportedly made by Thomas Butler himself in 1884.

(image kindly provided by the Science Museum)

The private Farren Collection in Melbourne, Australia, also has an Omnicycle. According to its curator Paul Watson, this came from Bathurst in NSW, which seems to have had a strong cycling scene in the 1880s, including the British champion Dr Herbert Cortis as a member of the Bathurst Cycling Club. We found three photos of this machine on Robert Štěrba’s amazing cycling history website – one of the machine as a whole, the second of the treadle mechanism and the third of the Butler patent gearing.

Paul Watson also tells us that the Farren Collection used to have another original omnicycle that came from Geelong in Victoria which was subsequently donated to either the Victorian or Australian museum.

We also came across an 52 inch Omnicycle that used to be housed in the now defunct Canberra Bicycle Museum. According to Paul Watson, this was a replica made by Rob Dewhurst, who also did some restoration work on the original Omnicycle which is now in the Farren Collection, and used this as a reference for the replica. Its current whereabouts is unknown.

(http://hpv.tricolour.net/photos/Catalogue%20of%20bikes.pdf)

That’s what we have discovered so far about surviving Omnicycles. If you have any information about these or any others, we’d love to hear from you.

Postscript

Edwin Butler passed away on 24 February 1931 aged 81 years. Reporting his death, the Reading Standard described him as a ‘wit and pioneer cyclist’. His brother Tom died in January the following year at the age of 78. His death notice, also published in the Reading Standard, hailed him as a ‘clever engineer’ who ‘in the early days of the cycle invented the omnicycle’.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply indebted to Colin Kirsch, curator at the fabulous Online Bicycle Museum, for editing an earlier draft of this article, for providing historical source materials, and for his invaluable help in locating the French and Australian Omnis.

In addition to Edwin Butler’s diaries, the Online Bicycle Museum, Grace’s Guide to British Industrial History, Internet Archive and www.sterba-bike.cz were our main research sources for this article.

Any errors or omissions are those of the author (Simon Vollam).